El Paso, Texas is a border town if there ever was one. Together with Juarez, Mexico, it is one large, poor, dusty city of two and a half million cut down the middle by the Rio Grande. The drive out of El Paso, Texas to the hill takes you through an incredible, high arid desert landscape. Vistas that stretch for hundreds of thousands of acres as far as the eye can see, and a sky overhead that extends even farther. Look ahead and you can see 100 miles into New Mexico. Look behind and you can see 100 miles into old Mexico.

The landscape, and the storms that often blow through it, are biblical in scale. “I love the taste of this sand in my mouth,” Jim muses. “It’s very Old Testament. From this very spot, if we were to continue driving due east, we would end up in Jerusalem. How much gas do you have?”

First you go to El Paso, which is nowhere by art world geographical reckoning. A few hours of driving gets you to Valentine, Texas, which is nowhere by most anybody’s reckoning. Turn off the road somewhere near past Valentine and head out into the desert on some faint tire tracks in the dirt, and you are at The Hill.

Just what the hill is is difficult to pin down, even for Jim, who made it.

“The hill is my whole life. I don’t know what to say beyond that. I guess everything I do leads me back to this hill. It’s everything for me. I dream about it.”I dream about the hill a lot. I don’t know how to go into that. That is where the hill is, not where we are going. It’s a fingerprint. We all leave fingerprints on the earth, I suppose.”

“Someone once called it a collect call to the future.”

The road that took Jim to the desert stretches through the entirety of his 56 years. It began with his conservative Protestant mid-western upbringing, continued through law school, traveling in Africa, a Christian monastery in France, work for the United Nations in New York City, a junk yard ion Staten Island where he made his home and first began to work with large-scale junk art, and his subsequent home and studio in a chicken coop and ladies underwear factory in upstate New York.

But more than anything, the hill took shape in small hours of the mornings in the abandoned shipping piers on the west side of lower Manhattan, which in the brief period between Stonewall and AIDS became the dark and anonymous stage for one of the most incredible sexual theaters the human race has ever known. Dark and derelict buildings with huge rooms and high ceilings, filled with every kind of junk, and men, in every state of undress and every kind of sexual act. For many of the men who participated, it was a soul-searing experience that shaped them for the rest of their lives. None were affected more than Jim, who participated in characteristically startling ways: once, in a dark and shadowy room filled with silent shadows and the muffled sounds of sexual pleasure and agony, Jim stood and recited Yeats with an declamatory, Shakespearean voice.

The whirl of days at the United Nations, nights at the piers, and every moment in between spent working on art at the junkyard — at some point it all became too much for Mr. James Magee. He decided to devote his life to art, but further resolved that in order to do so he would have to get as far from the art world as he could. Thus began the trek that eventually landed Jim in nowhere, Texas, where he found the hill he had seen in his dreams, bought it, and began a work that has taken over 20 years and is still unfinished. He figures it will not be complete for another 10 or 15.

“I enjoy working on things for long periods of time, whether people see them or not. My process is very slow, and the hill, or whatever I have done out there, is amenable to that.”

The site seems more like an archeological dig than a gallery.

“I went out with a string and compass, and staked out where it would be. With that everything else was set. We had no architect, no blueprints, the entire construction was laid out with me pacing and using a string and a transom, that’s it.”

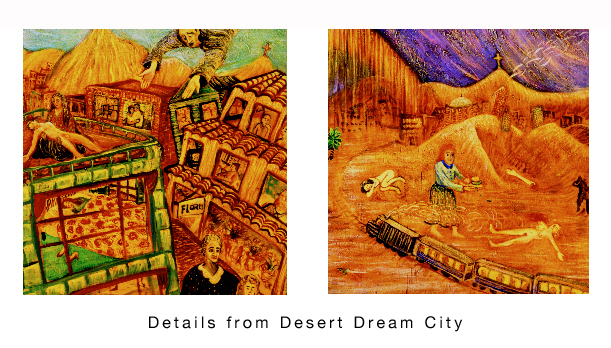

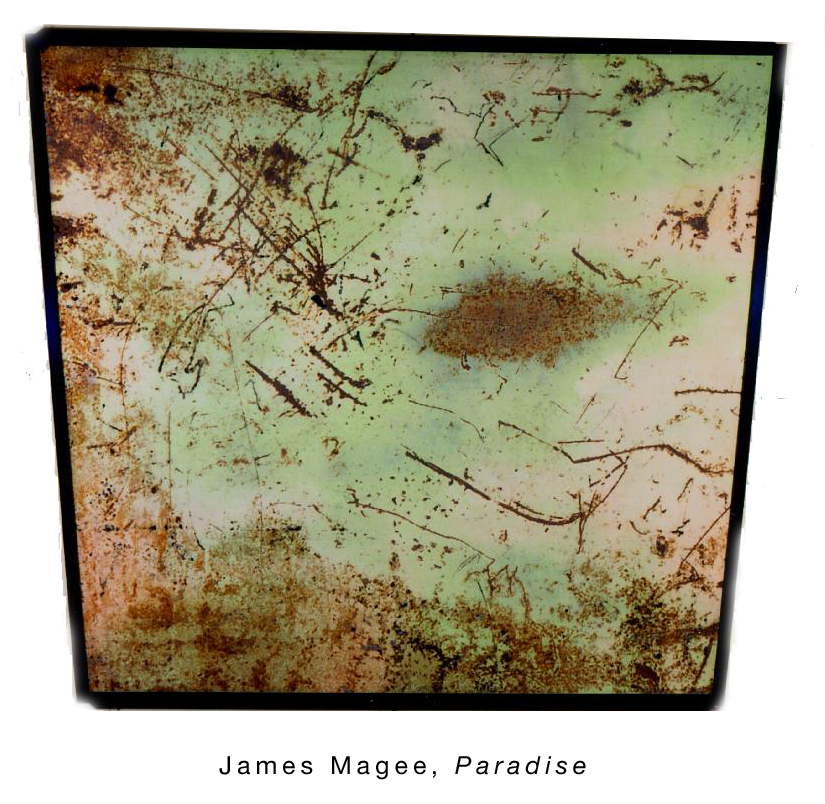

The art defies description. Giant works of many tons each. Steel and iron triptychs on huge ball bearings. Studies in rust and decay and debris. Acid and honey. Beeswax and burnt rubber. Paprika and cold-rolled steel. Barbed wire and pig bone.

This is only art I have ever seen that always leaves the viewer speechless, groping for but never finding an adequate reaction. This is partly because it is so surprising in scale and composition, partly because it is so stunning in detail and execution, but mostly because it is so intensely and profoundly personal. Going to the hill is not like going to view art, but going not only into the dreams and the imagination, but also the bones, blood and muscle of James Magee.

Everything seems to be constructed of industrial debris, but in truth there are very few found objects in the works. Jim makes his own junk from scratch, welding and machining and casting and pouring it, rusting and cracking and breaking and burning it.

“You can’t find all the found objects that you need. I do use found objects as such, but people start from different points. Its their makeup that decides how they begin. I begin in my head, from my gut. I can’t find my sketches readily along a roadside.”

Jim gives these works titles, which often run on to several pages of text. Poems, really. His idea is that you stand in front of one of his works, and as you view it he stands behind you and whispers the title in your ear. If the titles alone were the sum total of his artistic output, Jim would be an American poet of the first order.

Very few people have seen the hill over the decades Jim has worked on it. It is not open to the public, not advertised, has no art biz huckster hustling it and pushing it, boasting of its import. Without Jim taking you there, one could not even find it. Yet he has poured his life into it, tens of thousands of hours of labor, tens of thousands of dollars of materials. It is a life’s work, more so than any other work by any other artist I have known. And it has only been seen by a handful of people.

Jim has very deliberately created a work that can never be sold, will never acquire any market value, can never be moved, and cannot even be found unless Jim takes you there.

One of the earliest visitors to the hill was May, who now runs the truck stop down the road. A former truck driver who prides herself on being the self-appointed Mayor of the “town” of 3 (or 4) (or 5), she describes the works on the hill as “pyramids. Is that good enough? It’s all of that. I think he’s got the same concept.”

“He wanted to know if he could borrow some water to put the cement together. I told him sure.” In another couple of years, he said “Do you think you could loan me some more water to build some more?” I said, “Sure, why not?” Then he said he wanted to build three this time. I said, “Three? What happened, did your ship come in?”

Of course all the people in this area think he’s a nut. I’ve even had some people think he’s a devil worshipper because of the pedestals up there. They’ve been up there peeking, they peek through them doors. In place of them thinking its something to put art on they think its some kind of pulpit or something. They said, “Well, have you seen his work?” And I said, “No not really, but if I just call him he’ll show me.” And they said, “Oh May don’t go.'”

I think he’s great. I don’t know how to describe it, one of a kind, I guess. Maybe [they are about] life.

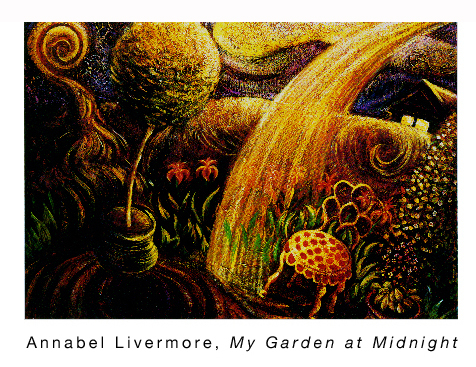

There is another El Paso-based artist who is very close to Jim. In stark contrast to Jim, she has done quite well in the art market over the last decade or so, an elderly recluse named Annabel Livermore. Annabel is a retired school librarian who is spending her retirement painting watercolors of flowers and oil paintings of fantastic landscapes that seem to come more from the Mexican side of the border than the gringo side.

Annabel has risen from total obscurity to stardom in the Texas art world. Her dealer, Adaire Margo, says that Annabel is the only artist her gallery has ever shown who actually sells out entire shows. Her work has been featured in two books, one by the noted English art critic Edward Lucie-Smith on flora, the other a survey of American landscape painters, in which she is presented as a sort of spokeswoman for the American Southwest.

Annabel decided to celebrate her success by donating a vase of flowers to each patient in the Thomason Hospital in El Paso every Christmas. An accompanying card reads, “With this card I wish you health and happiness, Annabel Livermore.” Eventually, the hospital invited Annabel to design and paint a non-denominational chapel for the facility, which she did.

One of the most remarkable things about her work is the passion it evokes among Annabel’s fans. Adaire Margo:

She has really touched people’s heartstrings here. She has processed the border region in a very unselfconscious way. People look at it and say, “This is who we are, we love this work.”

We started from scratch. Annabel didn’t have any real notoriety or name. She didn’t even have a real resume, like the arts schools that she went to or the museums that she was in. Her resume was a school librarian’s. But people bought the work anyway, even though it wasn’t really tied to the art world. I mean, it was shown in art galleries, but it wasn’t with assurances of Annabel rising to stardom. People loved it and they bought it because they loved it. And they are not all wealthy people. One woman bought an Annabel for $5000 and pays us $100 a month. She’s a schoolteacher.

What is perhaps most remarkable about Anabel’s success is that it has not been undermined as it has gradually become known that she does not exist in any conventional sense, but is the creation of Jim Magee. But “creation” is not the right word.”Persona” is the word her dealer eventually settled upon. Personality? Alter ego? Perhaps the precise word does not exist.

Years ago, a much younger Jim Magee was living in upstate New York and doing his first experiments with the gnarled, rusted, almost terrifying art that would fill his life for the coming decades. He was the subject of an experimental film in the same vein by American film maker Rod McCall, which he sent to the brothers in a Christian monastery in France he had spent some time at.

The monks wrote back their response: “We’re sorry you feel so bad. We suggest you take some time to look around and appreciate God’s good works.”

Jim went straight out with canvas and paints and painted some flowers. He found the exercise profound, but so totally removed from the other work he was doing that he did not see how one person could work in both directions at the same time, and Annabel Livermore was born.

Among the many things that Annabel is, there are a few things she is not. She is not a marketing scam. And she is not a drag queen. Annabel has her own studio, in a detached room behind the garden at Jim’s El Paso home. And her association with Jim Magee has been accepted by her fans in El Paso, one of the most conservative cities in one of the most conservative states in the US. In fact, one of her biggest supporters has been Laura Bush, former First Lady of Texas and currently the First Lady of the United States. “She loved Annabel,” Adaire remembers, “and saw the work, and then later invited Annabel to exhibit her the work in her offices at the state capitol in Austin.”

Janis Keller is an El Paso socialite whose husband Bobby does real estate deals across the border in Mexico. She speaks with a long Texas drawl and belongs to the El Paso Country Club. She and her husband have a beautiful split level home from which Bobby leaves to his deals in a shiny SUV. Once a year Janis and Bobby take their kids on a gambling vacation in Las Vegas. Janis is such a passionate Annabel fan, it would b fair to say she has in part built her life around Annabel. Not only is Janis the proud owner of several of Annabel’s works, but she changes the flowers every day at the hospital chapel, and puts together a group of ladies to deliver Annabel’s flowers at the hospital each Christmas. She knows the connection between Jim and Annabel, accepts it and lets it go.

The first time I met Janis was at the hospital chapel. The walls of the chapel are lined with Annabel’s watercolors, the frames of which are on hinges. Small bits of paper and pencils sit on ledges below, and visitors are invited to leave prayers and thoughts for their loved ones in cubby holes behind the paintings. Janis clears out the prayers when she changes the flowers each day, and now has several thousand prayers. “What are you going to do with them all,” I ask.

“Well, I know what I think we should do. I think Annabel should make a calendar with 12 of her nicest works, one for each month, and we will pick 365 of the nicest prayers and put one on each day.” Janis turns to Jim, who is seated next to me.”So Jim, if you would, please tell Annabel I have this calendar idea.”

Jim says nothing

Now that link between Jim and Annabel has become more broadly known in Texas, some of Annabel’s fans have been more exposed to the work of Jim Magee. Laura Bush herself has been to the hill, with an entourage of secret security and a police helicopter overhead. And though Jim’s work is difficult for Annabel fans, they give it their full attention, and seem to remain unshakable in their allegiance to Annabel, regardless of their reaction to Jim. Janis Keller:

[Jim’s] sculptures are so harsh to me, they scare me. I can see myself, if I could, watching Annabel paint, and Annabel would be painting, and it would be Jim. But I find it hard in my mind to picture Jim doing Jim Magee’s work. What would he be like? I wonder, I don’t know. Would he be attacking something viciously, or putting each thing very carefully down, like everything obviously is, but with all of the force of the metals he uses and all of that kind of thing, that’s really harsh to me. If I ever got to see either one of them do the real work, I’d rather see Annabel than Jim.

I find Annabel’s work beautiful, Jim’s titles extraordinary, and the hill deeply profound. But what I love most of all is the package as a whole. Jim’s path has cut a dizzying trail through locales and social settings as disparate as the United Nations bureaucracy, the Manhattan art world, the gay Manhattan underworld, the genteel world of El Paso socialites, and the isolation of desert. He has worked in video, sculpture, architecture, steel and iron work, painting, and large-scale construction, without ever thinking about “mixed media.” He has become two people without trying to be weird or schizophrenic.

He has struggled every inch of the way: with difficult materials like rust and steel, with sandstorms and blistering heat, with his own personal demons, and with a long and terrible illness which has left him with an amputated leg and an extremely uncertain future. Through it all he has uncompromisingly followed connections and imperatives he felt deeply, even if he was not sure why. What he has done in short is lead a creative life.

Interview by Bob Ostertag